Profits Poised for Growth

October 12, 2020

Brian S. Wesbury – Chief Economist

Robert Stein, CFA – Dep. Chief Economist

Strider Elass – Senior Economist

Andrew Opdyke, CFA – Economist

Bryce Gill – Economist

COVID lockdowns crushed the economy in the first half of 2020, with real GDP down 5.0% at an annual rate in the first quarter and 31.4% at annual rate in the second quarter, the latter of which was the steepest drop in real GDP for any quarter since the Great Depression in the 1930s.

But for the third quarter, the US is tracing out a V-shaped bounce and likely grew somewhere between 30 – 35% at an annual rate, the fastest increase in real GDP for any quarter since at least World War II. The rebound is due to two things…a shift in activity toward businesses that were able to stay open because they were “essential” or found new ways of getting things done, and the actual reopening of businesses in recent months. Still, because many types of businesses are regulated, and because some companies will never reopen, it looks like it’ll take until late 2021 for real GDP to fully get back to where it was preCOVID-19.

Yet, stock market investors are not buying shares of GDP, they’re buying shares of specific companies providing specific goods and services, many of which have had and will have robust profits or healthy rebounds in profits to entice investors.

Economy-wide corporate profits peaked in the fourth quarter of 2019 but then fell 12% in Q1 and another 10.3% in Q2. Converting these figures into annualized changes, profits declined at a 37.6% rate in the first half of 2020, versus a total 2quarter drop of 19.2% for real GDP.

In other words, profits dropped faster than the overall economy.

Look for this process to go in reverse for the third quarter and beyond.

First, it’s normal for profits to grow faster than the economy in the early stages of economic recoveries. The profit share of GDP bottomed at about 7% in both the 2001 and 2007-09 recessions, but eventually peaked north of 12.0% of GDP. They are now 9.4% of GDP

Second, the labor share of GDP (wages, salaries, and fringe benefits) surged in the first half of the year as firms reduced payrolls rapidly but not quite as rapidly as production fell. Many employers operated on a forward-looking basis, realizing they could ill afford to layoff workers who they figured they would want and need when the crisis passed. But that also means less of an increase in payroll costs as the economy heals.

Third, many firms have trimmed other costs, beyond payrolls, supporting the bottom line. Think less travel and less office space, in particular. Yes, of course, airlines, for example, get hurt when fewer people travel for business, but they can trim costs, so a dollar saved by the firm for which someone is traveling doesn’t need to mean a full dollar less in profit for the firm providing travel services.

Bottom up forecasters have been predicting record levels of overall corporate profits next year, and we concur from a top down approach. Bottom line, the rise in stocks is not based on fantasy, but the fact that profits and low interest rates continue to reflect undervalued equity prices for most industries.

Consensus forecasts come from Bloomberg. This report was prepared by First Trust Advisors L. P., and reflects the current opinion of the authors. It is based upon sources and data believed to be accurate and reliable. Opinions and forward looking statements expressed are subject to change without notice. This information does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security.

https://www.ftportfolios.com/Commentary/EconomicResearch/2020/10/12/profits-poised-for-growth

The Fed Gambles on Inflation

October 5, 2020

Over the past couple of decades, the Federal Reserve has coalesced around an idea about inflation that is little more than theoretical, with no real data to back it up. That “idea” is that 2% inflation is the “correct” amount of inflation.

The target is not just a one-year target, it is seemingly a permanent, long-term target. We find this idea very problematic. For example, the Fed’s favorite measure of inflation, the PCE deflator, has averaged 1.5% over the past decade. But the Fed now says it could let inflation in the future run high so that the long-run average rises to 2%. No one knows exactly what this means, but one interpretation is that the Fed is willing to have inflation run at 2.5% for the next ten years so that the 20-year average is 2%.

Really? Why? If we look back over the past ten years, low inflation didn’t hurt the economy, it helped it. Unemployment had fallen to 3.5% in February, the lowest since the 1960s. Yes, we know we’re just emerging from the problems related to COVID-19, but that’s an outside shock to the economic system, not something monetary policy can plan for ahead of time. It had nothing to do with the Fed or the level of inflation.

We have always believed that the underlying reason for the existence of the Fed was to maintain a stable value of the dollar. The most stable environment is one with no inflation. As Steve Forbes has always said, if a carpenter shows up at a job site and his yardstick is a different length than it was the day before, it is awfully hard to build a house, maybe impossible.

The same is true for the value of the dollar. It’s far more complicated to make an investment, build a plant, or sell goods to a foreign country if the value of your currency changes over time making the value of revenues and investment change with it.

This is what worries us about the commitment to 2% long-run inflation. No one knows exactly what it means, or for that matter, why it is appropriate. Again, inflation averaged 1.5% over the past ten years with no serious consequences to the economy. By allowing inflation to average 2.5% over the next ten years, how does that change the past? The answer: it can’t!

What it does do is change the future. In essence, the Fed is saying they really don’t have a 2% inflation target, they have a target above 2% for the foreseeable future. And this is worrisome. The money supply has exploded in recent months as the Fed has monetized federal debt. Inflation is on the way higher. For example, this year the Fed said the PCE Deflator would be 0.8%, but it is already 1.4%, and looks more likely to rise than fall.

And if it rises to 2.5%, the Fed will say that is OK, because the average over some period of time (which it can make up by using any number of years of history) is still 2%. Back in the 1970s, the Fed kept saying inflation was rising, but it was all because of temporary factors (like oil) and it would fall later. But, once inflation is out of the bottle, it doesn’t come down until the Fed tightens, like Paul Volcker did in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

So, letting inflation rise above 2% is potentially very dangerous. The Fed has created an artificial target and given itself an excuse for causing more inflation. If 2% is really the target, the Fed should claim victory when it is less than that and fight to keep it from rising above.

Unfortunately, the Fed is making arguments about inflation that are designed to give it freedom to do whatever it wants and that may actually lead to a devaluation of the US dollar. This is a violation of the real reason for the Fed and it worries us about the future of inflation in the United States.

Consensus forecasts come from Bloomberg. This report was prepared by First Trust Advisors L. P., and reflects the current opinion of the authors. It is based upon sources and data believed to be accurate and reliable. Opinions and forward looking statements expressed are subject to change without notice. This information does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security.

https://www.ftportfolios.com/Commentary/EconomicResearch/2020/10/5/the-fed-gambles-on-inflation

Full Recovery Requires Reopening

September 28, 2020

Brian S. Wesbury – Chief Economist

Robert Stein, CFA – Dep. Chief Economist

Strider Elass – Senior Economist

Andrew Opdyke, CFA – Economist

Bryce Gill – Economist

With the presidential election just over a month away, prospects for another round of fiscal stimulus seem to be dwindling. The recent death of Justice Ginsburg and the rapidly approaching election have shifted the Senate’s gaze.

Conventional wisdom is worried that a lack of additional stimulus, and the potential for a drawn out and contested election, could impede the economic recovery. And some of those fears seem to be reflected in the stock market recently, with the S&P 500 having fallen 7.9% from its high of 3588 on September 2, as of Friday’s close.

While we need to wait for August data on incomes, through July, the Commerce Department’s measure of personal income was 4.9% higher than in February, as government transfer payments – which the US borrowed from future taxes – more than fully offset declines in wages and salaries. Think about that for a moment. Even with the end of special unemployment bonus payments, there is likely more money in people’s pockets today than there would have been had the pandemic never happened!

Right now, any weakness in the economy is coming from the fact that many sectors (especially service-type activities) remain shut down or lightly used.

Spending on goods in July was up 6.1% from February, while spending on the more pandemic-restricted service sector was down 9.3% over the same period. Overall spending (goods plus services) remains down 4.6%. We doubt a full recovery can happen without a rebound in services. Additional checks can’t change Americans’ wants and desires. Instead, continued recovery is going to require states to push ahead with reopening in a responsible manner.

Take New York and California. Daily new cases are down roughly 92% and 66%, respectively, from the peak in these states. Deaths are down, 99% and 40%, respectively as well. Yet both still have some of the nation’s strictest pandemic-related restrictions in place. This, in turn, has held back their economic recoveries.

According to August data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, New York and California had unemployment rates of 12.5% and 11.4%, respectively, while the unemployment rate for the US excluding these two states was only 7.7%. If New York and California mirrored the nation’s unemployment rate, the result would be an additional 1.2 million Americans employed. New York and California combined have 18% of the US population, but 32% of all people receiving continuing unemployment benefits.

Just this past week, Florida (7.4% unemployment) and Indiana (6.4%) have fully opened their economies. These states, among many others, had lower unemployment than the national average, mainly because their shutdowns were less draconian.

The competition between states that open and those that don’t – at the political, business, sports, school, and even family level – will lead to even more opening of the economy in the months ahead.

For a self-sustaining recovery to fully catch hold, it is reopening, not additional stimulus, that is the key.

Consensus forecasts come from Bloomberg. This report was prepared by First Trust Advisors L. P., and reflects the current opinion of the authors. It is based upon sources and data believed to be accurate and

reliable. Opinions and forward looking statements expressed are subject to change without notice. This information does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security.

https://www.ftportfolios.com/Commentary/EconomicResearch/2020/9/28/full-recovery-requires-reopening

The Long Slog Recovery!

September 21, 2020

Brian S. Wesbury – Chief Economist

Robert Stein, CFA – Dep. Chief Economist

Strider Elass – Senior Economist

Andrew Opdyke, CFA – Economist

Bryce Gill – Economist

The second quarter of 2020 was the mother of all economic contractions. Real GDP shrank at a 31.7% annual rate, the largest drop for any quarter since the Great Depression.

However, based on the economic reports we’ve seen so far, it looks like the third quarter will be the mother of all economic rebounds. Even if industrial production and retail sales are flat – unchanged – in September, they will still be up at 37.6% and 60.1% annual rates, respectively, versus the second quarter average. Total private-sector hours worked would expand at a 25.6% annual rate. Housing starts would be up at a 218% annual rate. (No, that last one is not a typo.)

The GDPNow tracking model, created but the Atlanta Fed, is forecasting that real GDP grew at a 32% annual rate in Q3. We’re waiting for data on inventories and net exports (which may pull down GDP growth) before committing to a growth rate over 25%. But, either way, it’s going to be the fastest real GDP growth for any quarter since World War II and we all knew it was coming.

The first thing to recognize is that even if the real GDP growth rate in the third quarter equals or exceeds the percentage drop in the second quarter, the economy is still in a very big hole. To illustrate this point and putting aside that GDP figures and percentage changes are annualized (which is a whole other issue), let’s take a company that produces 100 dresses each quarter. If production drops 20%, that means it goes down to 80 dresses. If production then goes up by 20%, that growth rate is from a lower base (80, not 100), so a 20% gain just gets you back to 96 dresses. It’s harder to grow out of a hole than it is to dig one.

The bottom line is that a full economic recovery in the US is still multiple years away. The surge in growth in the third quarter is largely related to many businesses going from a total lockdown to a new COVID-19 normal. Production and construction six feet apart, no fans in the stands, and 50% occupancy. Meanwhile, many small businesses (and some not so small) have simply disappeared.

This suggests that although growth should continue after the third quarter, it’s not going to be nearly as fast. You can only re-open your business once, not again and again (unless lockdowns happen again, which would send the economy back into negative territory).

We don’t think we get back to the level of real GDP we saw in late 2019 until late 2021. And that’s really not a full recovery because, in the absence of COVID-19, the economy would have grown 2% or more, per year, in the interim. If we define a “full recovery” as getting back to an unemployment rate at or below 4.0%, we’ll probably have to wait until 2023.

The pace of the recovery in 2021-22 will depend not only on the course of COVID-19, as well as development of vaccines, and therapies, but also public policy. Reducing overly generous unemployment benefits, even if gradually, would help get many back to work.

Some investors might be concerned about tax and regulatory increases in 2021, but it appears increasingly likely that any tax increases would not kick in until at least 2022 and maybe 2023.

If Joe Biden wins the Presidency and the Democrats take the US Senate, it would likely be by a very narrow majority. In that instance, we would imagine at least several Democrats balking at immediately imposing tax hikes. Remember, when President Obama took office in 2009, the Democrats had 59 seats in the US Senate, and taxes didn’t go up until 2013. This was because Democrats were hesitant to hike tax rates when unemployment was high and the economy was slowly recovering from the Financial Panic of 2008-09.

In addition, a President Biden would likely face a federal judiciary that more strictly limits federal regulators to issuing rules that stick to the laws passed by Congress and don’t go beyond. This makes executive orders “increasing” the power of regulators harder to push through than those that “limit” those powers. And the Supreme Court may get a new member soon.

Either way, don’t expect the rapid growth in the third quarter of this year to last. It’s going to be a long slog back.

Consensus forecasts come from Bloomberg. This report was prepared by First Trust Advisors L. P., and reflects the current opinion of the authors. It is based upon sources and data believed to be accurate and reliable. Opinions and forward looking statements expressed are subject to change without notice. This information does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security.

https://www.ftportfolios.com/Commentary/EconomicResearch/2020/9/21/the-long-slog-recovery

Inflation and the Fed

September 14, 2020

Brian S. Wesbury – Chief Economist

Robert Stein, CFA – Dep. Chief Economist

Strider Elass – Senior Economist

Andrew Opdyke, CFA – Economist

Bryce Gill – Economist

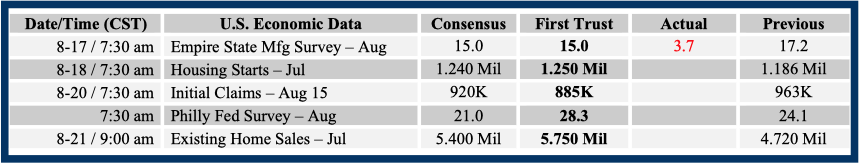

As we near the end of the third quarter, key economic reports will be released that will influence our forecast for third quarter real Gross Domestic Product. It will be a very strong quarter. We expect a 25% “annualized” growth rate in Q3. Using just the data that have already come in so far, the Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank’s GDP Now Model says 30%. Either would be a record quarter for the US economy, but still an incomplete rebound from the shutdown collapse in the first half of the year. This week industrial production, retail sales, housing starts, and a weekly report on unemployment insurance are on tap.

Also this week, the Federal Reserve will hold a two-day meeting, which ends on Wednesday. The Open Market Committee will revise its economic forecasts, reveal its expected path of short-term interest rates, and Chairman Powell will hold a post-meeting press conference.

We anticipate a focus on the Fed’s willingness to let inflation run higher than its 2.0% target to make up for periods when it has run below 2.0%. For the record, this is not a new policy. The Fed has talked about it for years. But what does it really mean? The Fed’s favorite measure of inflation, the PCE deflator, has grown at a 1.5% annual rate in the past ten years. So, in theory, the Fed could let it grow at an annual rate of 2.5% for the next ten years and claim consistency. And because the Consumer Price Index typically grows faster than the PCE deflator, that could mean the CPI increases at about a 2.75% annual rate.

Back in June, the median forecast among Fed policymakers was that PCE prices would rise 0.8% in 2020 (Q4/Q4), which already appears too low. We’re estimating an increase of 1.4%, which is only a hair below the 1.5% increase in 2019.

The Fed’s June forecasts for inflation in 2021 and 2022 also look too low, at 1.6% and 1.7%, respectively. The M2 measure of the money supply is up 23% in the past year, the fastest rate on record, and much above its growth rate after the first use of Quantitative Easing between 2008 and 2015.

Meanwhile, consumer spending has revived much faster than production, with retail sales up 2.7% versus a year ago in July, while industrial production is down 8.2%. The reason for the gap is unprecedentedly generous government transfer payments, which, in the four months ending in July, were up 77% versus a year ago. You show us a country where people can spend more without producing more, and we’ll show you a country that is heading for faster inflation.

But with the Fed willing to let inflation rise, we don’t think it’s going to lift short-term interest rates anytime soon. This, in turn, will hold the entire yield curve down. At least for the near- to medium-term.

But what happens if, as we expect, inflation has clearly and persistently outstripped the Fed’s long run 2.0% target? Will the Fed act to bring it back down? Will it let it run? The Fed has embarked on a dangerous game. Let’s hope it has not forgotten the hard lessons learned from the late 1960s through the early 1980s. For now, rates will stay low. But no country can print its way to prosperity, nothing is free. The stakes are very high.

Consensus forecasts come from Bloomberg. This report was prepared by First Trust Advisors L. P., and reflects the current opinion of the authors. It is based upon sources and data believed to be accurate and reliable. Opinions and forward looking statements expressed are subject to change without notice. This information does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security.

https://www.ftportfolios.com/Commentary/EconomicResearch/2020/9/14/inflation-and-the-fed

Positive Policies to Cut the Debt Burden

Aside Posted on Updated on

September 8, 2020

Brian S. Wesbury – Chief Economist

Robert Stein, CFA – Dep. Chief Economist

Strider Elass – Senior Economist

Andrew Opdyke, CFA – Economist

Bryce Gill – Economist

When government forces businesses to close (even if it is for a pandemic), it’s a “taking” in the legal sense. And we can think about $3 trillion in extra federal spending as “just compensation” to businesses and workers for that taking. Basically, we decided to borrow from future generations in an attempt to stop a virus and save the economy.

Federal borrowing is already more than 100% of GDP and politicians are debating how much more money to borrow as shutdowns drag on. Some of this potential borrowing, up to $1 trillion, is for direct state bailouts. And it appears some of that borrowing is to bailout states for problems that already existed. For example, in Illinois, unfunded pension obligations were roughly $200 billion before COVID hit. Illinois politicians are not letting a crisis go to waste and want to get bailout money now.

Those who worry about federal spending and the “moral hazard” of rewarding bad financial behavior by states look at a bailout as a huge mistake. The question is: Could there be anything positive that comes from this? What policies could the US put in place to limit the damage to future generations from all this borrowing? If we are asking our children and grandchildren to pay for this, are there things we can do that boost growth and limit the odds of more bailouts ahead?

We think there are.

First, the Treasury should issue 50- and 100-year Treasury bonds to finance Coronavirus debt. While the virus will pass, the economic costs will not and should be financed over a long period of time.

One of the reasons this has not happened already is that, in the normal budget process, issuing longer-term debt at higher interest rates than short-term borrowing rates increases debt costs and therefore total government spending. This takes away short- term budget dollars that politicians hope to spend on other things, so they don’t like it. But these days, nobody in Washington, D.C. seems to care about adding to spending. So, lock-in the financing costs for decades to come. After all, that’s realistically how long it will take to pay it back.

Second, if US taxpayers are going to bail out states, we should force states to change policies so bailouts are less likely in the future. This means the President and Congress should ask for three changes in the way state and local governments manage their affairs.

Taxpayers should demand that states immediately shift to defined contribution pension plans (like 401-K’s) from defined benefit plans. The private sector has already done this; states should too. It limits the liabilities of state and local governments and pushes government workers to think more about their own retirement rather than putting the burden on taxpayers. If taxpayers are going to bailout Illinois for running up $200 billion of unfunded pension debt, they deserve to know it won’t happen again.

Taxpayers should require any states getting a bailout to provide universal state-wide school-vouchers so that parents can choose where their kids go to school with the property taxes they already pay. Right now, private schools in many states are open for in-person education, while public schools are not. The incentives are all wrong and vouchers will adjust those incentives.

Any state that gets a bailout should be forced to pass a Right-to-Work law and follow Wisconsin’s example of making Union dues truly voluntary, with no gimmicks about when a worker has to give notice to stop paying dues. Unions support more pay and bigger pensions for government workers with campaign donations to government officials. This helped create the budget problems that state and local government currently have today and government workers have not been hit as hard by shutdowns as private sector workers.

If taxpayers need to spend $1 trillion to bail out state and local government for decisions made prior to (and during) COVID, and these states are unwilling to open up their economies today, these states should be willing to make changes that will limit the chances of similar problems recurring in the future.

And if Washington, D.C. made these changes a requirement to receive bailouts, it would help offset the financial burden that federal taxpayers are being asked to shoulder. Any bailouts should come with conditions. Every bailout of banks in 2008/09 came with conditions, why shouldn’t states be required to do the same?

Consensus forecasts come from Bloomberg. This report was prepared by First Trust Advisors L. P., and reflects the current opinion of the authors. It is based upon sources and data believed to be accurate and

reliable. Opinions and forward looking statements expressed are subject to change without notice. This information does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security.

S&P 500 3650, Dow 32,500

August 31, 2020

Brian S. Wesbury – Chief Economist

Robert Stein, CFA – Dep. Chief Economist

Strider Elass – Senior Economist

Andrew Opdyke, CFA – Economist

Bryce Gill – Economist

If you pay close attention to our stock market forecasts, the title of this piece will look familiar.

At the end of 2019 we made the same exact forecast for the end of 2020 — the strangest year in our lifetimes, and it’s not even over. Compared to most analysts, this was a very bullish call. And then, when the market hit a pre-COVID19 peak of 3386 in mid-February, if anything we looked not bullish enough.

Then the bottom fell out of both stocks and the economy, struck by a combination of COVID19 and overly-strict government shutdowns. The S&P 500 bottomed at 2237 on March 23, pricing in an 80% drop in corporate profits from the year before, making our call of 3650 look obsolete.

About seven weeks later, on May 8, stocks had recovered back to 2930, but we figured 3650 was probably still obsolete, and so revised our year-end forecast for the S&P 500 to 3100. Still bullish, but from a lower base.

Then, only four weeks later, the S&P 500 had blown through our updated year-end target and was sitting at 3194. So we revised up our year-end target again, this time to 3350.

But, here we are at the end of August and once again stocks have blown through our updated target, closing last week at 3508. As a result, we’re moving our target back up to exactly where we started: 3650.

The key lesson in all this should be that it is a fool’s errand to try to time the market. Imagine being told on February 15 that the world was about to be hit by a widespread virus for which there was no known therapy or cure, that governments were going to react by shutting down massive swaths of their economies, and that US real GDP was about to drop at the fastest rate for any quarter since the Great Depression.

Then imagine you had to make a choice about how you would allocate your investments through year end. Many investors would have opted to sell their equities and not look back. But, as we now know, the better choice would have been to grit your teeth and stay invested.

In order to make a stock market forecast we use a model based on capitalized profits. Our model takes the government’s measure of profits from the GDP reports, divided by interest rates, to measure fair value for stocks.

To be cautious, we’re using the level of corporate profits in the second quarter, when they were down 20.1% from a year ago, and at the lowest level in nine years, a level from which they are very likely to recover in the third quarter and beyond. In addition, we are NOT using the current 10-year Treasury Note yield of 0.7%, which generates absurdly high targets for equity prices. Instead, we’re using a 10-year yield of 2.0%. And at that yield, with profits remaining at second quarter levels, our model says the S&P 500 is fairly valued at 4052.

In other words, we would not be shocked if stocks went even higher than our year-end target of 3650 and barring a major shift in public policy as a result of the election in November, expect further gains in the 2021.

Consensus forecasts come from Bloomberg. This report was prepared by First Trust Advisors L. P., and reflects the current opinion of the authors. It is based upon sources and data believed to be accurate and reliable. Opinions and forward looking statements expressed are subject to change without notice. This information does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security.

https://www.ftportfolios.com/Commentary/EconomicResearch/2020/8/31/sp-500-3650,-dow-32,500

The Housing Revival

August 24, 2020

Brian S. Wesbury – Chief Economist

Robert Stein, CFA – Dep. Chief Economist

Strider Elass – Senior Economist

Andrew Opdyke, CFA – Economist

Bryce Gill – Economist

The US economy got crushed in the second quarter, with the worst decline in real GDP for any quarter since the Great Depression. However, the long road to recovery has started and, for now, we’re penciling in real GDP growth at a 20% annual rate for the third quarter. Of all the parts of the US economy that have weathered the COVID-19 storm, none has been as resilient as the housing market.

Homebuilders started homes at a nearly 1.6 million annual rate in December, January, and February, before the Coronavirus and government-mandated shutdowns wreaked havoc. Those were the best three months since 2006 and showed that residential construction had finally fully recovered from the housing implosion that was a center point of the last recession.

Then, during the shutdowns, homebuilding plummeted: housing starts bottomed at a 934,000 annual pace in April, before gaining in May, June and July, hitting an almost 1.5 million pace last month.

We have been saying for the past several years that the fundamentals of the housing market suggest an underlying norm of 1.5 million housing starts per year. This is based on a combination of population growth (more people mean more housing) and scrappage (homes don’t last forever, either because of voluntary knockdowns, fires, floods, hurricanes. tornadoes,…etc.).

However, in the ten years ending in February (March 2010 through February 2020) builders had only started 1.011 million units per year. Part of this made sense: home builders started too many homes during the housing bubble and the only way to work off that excess inventory was to build fewer homes than normal. But, in our view, the inventory correction went too far. In the 20 years through February (March 2000 through February 2020), housing starts only averaged 1.265 million. Too low.

All of this suggests to us that home builders still need to make up for lost time, until the long-term average is closer to 1.5 million per year, which could mean reaching, and then averaging, a pace of something like 1.8 million starts for the next several years.

But it’s not only home building that’s recovered so quickly; home sales have revived, as well. Existing homes were sold at a 5.76 million annual place in February, the fastest pace since the housing bubble burst. Then sales plummeted in March, April, and May, bottoming at an annualized pace of 3.91 million, the slowest since 2010. Since May, however, sales have soared, hitting a 5.86 million annualized pace in July, even beating where we were in February.

Part of the recent gain was likely pent-up home purchases: people who wanted to buy earlier in the year but got temporarily thrown off track by the Coronavirus, massive economic contraction, as well as general uncertainty. But including the drop and the rebound, the average pace of sales in the last five months (March through July) is still slow, suggesting some further gains ahead. Ditto for new home sales, although neither existing nor new home sales will grow every month.

In terms of prices, we expect national average home prices to continue to grow, but with a wide dispersion. Dense cities hit hard by COVID-19, or which have seen social unrest (or both!), especially with the newfound ability to work remotely, are going to be relative losers; other metro areas are going to experience faster gains.

Yes, a Biden win in November could end up expanding the state and local tax deduction, helping some beleaguered cities. But that election outcome is not assured. The enlarged standard deduction would still mean fewer people itemize, and the Biden campaign wants to limit the “value” of itemized deductions to 28% (instead of a proposed top tax rate of 39.6%).

Bottom line: housing is going to be a significant tailwind for the US economy overall, but not everywhere.

Consensus forecasts come from Bloomberg. This report was prepared by First Trust Advisors L. P., and reflects the current opinion of the authors. It is based upon sources and data believed to be accurate and reliable. Opinions and forward looking statements expressed are subject to change without notice. This information does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security.

https://www.ftportfolios.com/Commentary/EconomicResearch/2020/8/24/the-housing-revival

Biden’s Tax Hike Agenda

August 17, 2020

Brian S. Wesbury – Chief Economist

Robert Stein, CFA – Dep. Chief Economist

Strider Elass – Senior Economist

Andrew Opdyke, CFA – Economist

Bryce Gill – Economist

Election Day is eleven weeks from tomorrow. In political time, this is an eternity. However, with the White House, about one-third of the Senate, and the entire House of Representatives on the ballot, this election is significant. Particularly because the two presidential candidates have such stark differences in policy perspectives, especially with respect to taxes.

Right now, the polling average puts former Vice President Biden about seven points ahead of President Trump. Data guru Nate Silver’s model says Trump has about a 30% chance of winning, which is right about where Silver put Trump’s odds on Election Day in 2016.

There are many reasons to doubt the polls, but it’s never a waste of time to think about what tax policy would look like with different Administrations and how that would affect the economy. This is especially true today, with many predicting dire market declines if a President Biden would achieve all his policy objectives.

If Biden wins, but the GOP keeps the Senate (right now, Republicans have 53 seats), the answer is easy: very little change. There is simply no way a GOP Senate majority would let Biden raise taxes. Tax hikes would be dead on arrival. The one change Biden might be able make is enlarging the deduction for state and local taxes. Many in the GOP would oppose, because it would lighten taxes more for residents of high-tax states than low tax states, but it still is a tax cut, not a hike.

What many investors are focused on is a scenario where Biden wins and the Democrats also take the Senate. In that scenario, the Democrats could use the special budget process on Capitol Hill to raise taxes permanently (meaning no natural sunset) with a simple majority, like President Clinton did in 1993.

Biden’s team has made plenty of tax proposals, but we’re going to focus on what we call the Big Five:

(1) Raising the top income tax rate on regular income back to 39.6% from 37%

(2) Raising the corporate tax rate to 28% from 21%

(3) Ending the step-up basis at death

(4) Treating long-term capital gains and qualified dividends as regular income for those earning over $1 million

(5) Applying the Social Security payroll tax on incomes over $400,000+

If the Democrats win the Senate, a Biden Administration is likely to be successful at raising the top dividends, because monies are taxed when a company earns profits and then again at the personal level. On long-term capital gains, the tax rate hasn’t been as high as 39.6% since the early years of the Carter Administration. That’s right, even Jimmy Carter thought that tax rate was too high!

Raising it that high would be a major disincentive for investors. And, given that the economy will be far from fully healed in 2021, we have serious doubts the Biden Administration could rally relatively moderate Democrats to such a tax hike. Remember, President Obama had 59 (and then 60) Senate votes and a large majority in the House, when he became president in 2009. And yet the Bush tax cuts he inherited were not unwound until 2013. And then, only partially.

The most aggressive proposal would be to impose the Social Security tax on regular earnings above $400,000. At present, that tax – 6.2% on workers, 6.2% on employers applies only on the ‘wage base” up to $137,700 in 2020, with the wage base going up each year based on wage growth.

Imposing an extra 12.4% tax would be a large disincentive for high-income workers. Tack that on top of the official 39.6% income tax rate, plus the 2.9% Medicare tax, and we’re at more than 50% (our math is factoring-in that some of the cost is paid by the employer, but the cost is ultimately borne by the worker). Then add in a top tax personal rate and the corporate rate, as well. We think lifting the top income tax rate back to 39.6% would hinder economic growth, but the effect would be small. That’s where the rate was under Clinton and in President Obama’s second term, and no recession happened in either period.

On raising the corporate rate to 28%, we suggest looking at the glass as half-full. Although we’d prefer the corporate rate to stay at 21%, did anyone seriously believe the corporate rate would stay there forever? The corporate tax rate was stuck at 35% from the early 1990s through 2017 and hadn’t been as low as 21% since the 1930s. The market is a discounting machine. If Democrats take back power and only raise it to 28%, that’s a win, in a way, because it means future policy debates on the corporate tax rate will range from 21% to 28%, not up to 35%.

President Biden also wants to apply a minimum profits tax of 15% on larger companies’ GAAP earnings, but we think this policy would have more bark than bite. The idea is that some companies are using legitimate tax maneuvers, like fully expensing investment, so they show very low (or no) taxable profits even though their GAAP earnings are high (because GAAP has them depreciate investment costs gradually over time). But companies would react by manipulating their books to show weaker GAAP profits, knowing savvy investors would see through the ruse. Companies could also spin off big investment projects to other companies that have large taxable profits, then lease the investment.

Although the Biden Administration would want to raise taxes on capital gains, we think he’d need more than a narrow 51 or 52 seat Senate majority to pass those changes and, even then, would have a tough time eliminating step-up basis at death or treating capital gains and ordinary dividends as regular income for those earning $1 million or more.

Eliminating the step-up basis at death would be an administrative nightmare for some heirs who inherit assets with no records of when the assets were originally bought or at what price. And many of these heirs are far from wealthy themselves. More likely, the Senate would reduce the exemption amounts for the estate tax, instead.

More troublesome from an economic growth perspective would be treating capital gains and qualified dividends as regular income for those making $1 million or more. For dividends, this would unravel about twenty years of tax policy reducing the double-taxation on rate of 13.3% for California, which may be going higher, and you have net marginal tax rates nearing 65%.

However, it’s unlikely the Biden Administration would be able to impose this extra layer of payroll tax. The special budget rules in the US Senate do not apply to any aspect of Social Security: not benefits and not taxes. Changing any aspect of Social Security requires going through “regular order” in the Senate, which means the proposal could be filibustered until it gets 60 Senators willing to support it. Fat chance!

The bottom line is that a Biden win coupled with Democrats winning the Senate would means taxes would go up. At this point, we don’t think they’d be raised fast enough or high enough to generate a recession by themselves. More likely, it means that after an early spurt of growth this year and perhaps next year, as the economy heals from the COVID-19 disaster, we’d be more likely to settle into a Plow Horse pace of economic growth (possibly with a hobbled hoof) like we had in 2009-16, rather than the somewhat faster pace of 2017-19.

But remember, one election does not make or break a nation. Before long, the 2022 mid-terms would loom large and the presidential election in 2024, with the American people ready to render electoral verdicts and make adjustments again and again.

Consensus forecasts come from Bloomberg. This report was prepared by First Trust Advisors L. P., and reflects the current opinion of the authors. It is based upon sources and data believed to be accurate and reliable. Opinions and forward looking statements expressed are subject to change without notice. This information does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security.

https://www.ftportfolios.com/Commentary/EconomicResearch/2020/8/17/bidens-tax-hike-agenda

A Healing Economy

August 10, 2020

Brian S. Wesbury – Chief Economist

Robert Stein, CFA – Dep. Chief Economist

Strider Elass – Senior Economist

Andrew Opdyke, CFA – Economist

Bryce Gill – Economist

It’s going to take years for the US economy to fully heal from the economic disaster brought about by COVID-19 and the government-mandated shutdowns which continue to limit economic activity across the country. When we talk about a full recovery, we don’t simply mean getting real GDP back where it was in late 2019; a full recovery comes when the unemployment rate gets back below 4.0%, and we don’t see that happening until at least late 2023.

Yet last week’s key reports on the economy clearly show we’re recovering. The ISM Manufacturing and Service indices, autos sales, and the employment report all beat expectations. The Manufacturing index came in at 54.2, while the sub-indices for new orders and production both exceeded 60.0 for the first time since 2018. The ISM Services index hit a robust 58.1 for July, the highest reading so far this year, including back in January and February when the economy was doing quite well. The new orders sub-index for services hit 67.7, the highest on record (dating back to 1997).

Meanwhile, consumers felt healthy enough to keep increasing auto purchases. Cars and light trucks were sold at a 14.5 million annual rate in July, the highest since February, when sales were 16.8 million annualized. To put this in perspective, auto sales bottomed at an 8.7 million annual rate in April, so this is one sector which is very nearly healed.

Of course, the big news for the week came with Friday’s employment report, which showed payrolls expanding faster than anticipated while the unemployment rate declined further. Nonfarm payrolls rose 1.763 million, while civilian employment, an alternative measure of jobs that includes small-business startups, increased 1.350 million. Combined with jobs gains in May and June, these figures show that we’ve recovered roughly 40% of the jobs lost in the carnage of March and April.

The best news was that both average hourly earnings and the total number of hours worked rose in July, with earnings up 0.2% and hours up 1.0%. Recently, these two figures have moved in opposite directions. At first, layoffs tilted toward lower paid workers, which meant average earnings for the remaining workforce were rising while total hours worked fell. Then, as hours rebounded and (disproportionately) lower-paid workers were rehired, the pattern reversed. Now they’re rising at the same time.

In addition, recent declines in unemployment claims signal that the improvement in the labor market is continuing. Initial jobless claims came in at 1.186 million in the latest week, 249,000 fewer than the prior week and the lowest level since March. Continuing claims for regular benefits fell 844,000 to 16.1 million, the lowest since April.

It’s still early – the initial report on real GDP growth in the third quarter won’t be released until October 29 – but plugging all these reports, as well as earlier ones, into our models suggests growth at a 15.0% annual rate.

But along with faster growth, we’re also going to see higher inflation. Broad measures of the money supply are growing rapidly, while the Federal Reserve remains committed to keeping short-term rates low as far as the eye can see. The Fed doesn’t think we’ll hit its 2.0% inflation target until at least 2023. We think inflation will get there, and beyond, before the calendar closes on 2021.

Consensus forecasts come from Bloomberg. This report was prepared by First Trust Advisors L. P., and reflects the current opinion of the authors. It is based upon sources and data believed to be accurate and reliable. Opinions and forward looking statements expressed are subject to change without notice. This information does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security.

https://www.ftportfolios.com/Commentary/EconomicResearch/2020/8/10/a-healing-economy